About ALS

What Is ALS?1,2

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, is a disease that affects parts of the nervous system that control voluntary muscle movements (the muscles that people move at will, like those of the arms and legs).

A-myo-trophic comes from the Greek language. "A" means no, "myo" refers to muscle and "trophic" means nourishment – "no muscle nourishment.”

ALS is referred to as a progressive disease, meaning the symptoms continue to get worse over time. People with ALS gradually lose strength in their muscles and become weaker, which can limit movement and the ability to live an independent life.

As ALS progresses, it will eventually affect muscles that control breathing, as well as chewing and swallowing food.

Currently, there is no cure for ALS. However, it's important to ask your healthcare provider(s) about treatment options.

As ALS progresses, it will eventually affect muscles that control breathing, as well as chewing and swallowing food.

Currently, there is no cure for ALS. However, it's important to ask your healthcare provider(s) about treatment options.

ALS and Your Body

How Does ALS Affect the Body?1

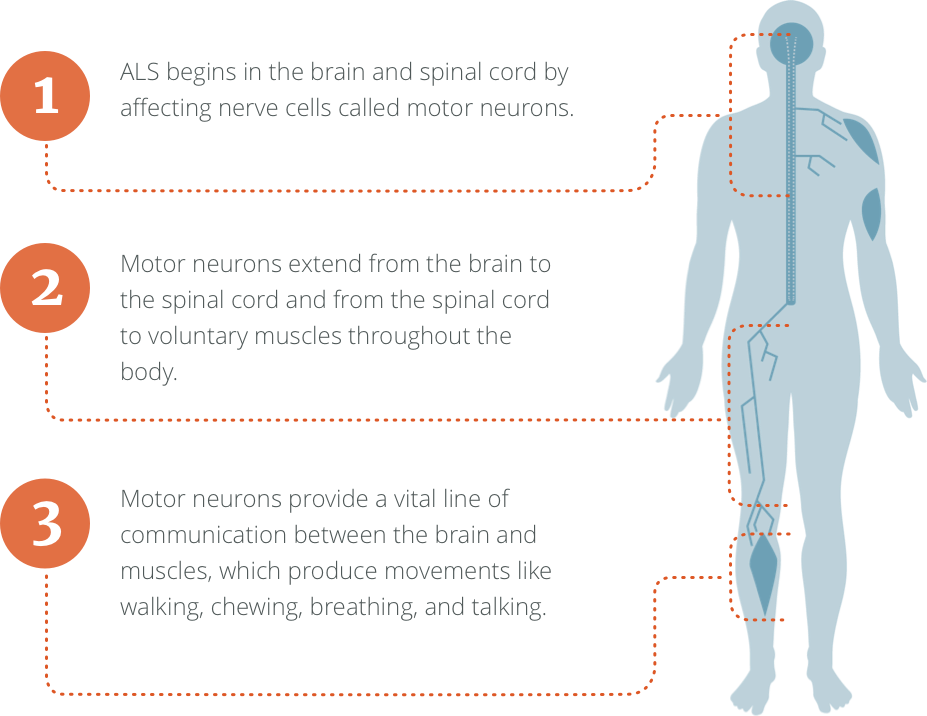

ALS begins in the brain and spinal cord by affecting nerve cells called motor neurons.

Motor neurons extend from the brain to the spinal cord, and from the spinal cord to voluntary muscles throughout the body.

Motor neurons provide a vital line of communication between the brain and muscles, which produce movements like walking, chewing, breathing, and talking.

In people with ALS, these motor neurons stop working. When this happens, the brain can no longer communicate with the muscles.

Over time, the brain loses its ability to initiate and control certain muscle movements, resulting in progressive weakness and paralysis. People living with ALS may eventually need assistance with speaking, eating, and breathing on their own.

Over time, the brain loses its ability to initiate and control certain muscle movements, resulting in progressive weakness and paralysis. People living with ALS may eventually need assistance with speaking, eating, and breathing on their own.

ALS spreads at different rates for everyone. Talk with your healthcare provider(s) about how your ALS is progressing.

Who Gets ALS?

ALS Can Affect Anyone

If you have ALS, it’s important to remember you’re not alone. ALS affects people of all ages, races, and ethnic backgrounds. ALS is the most common of the motor neuron diseases (MNDs), which is a wider group of disorders that can lead to loss of physical function.3

About 5000+ people in the United States are diagnosed with ALS each year.4

On average, a new case of ALS is diagnosed every 90 minutes.4

What Causes ALS?

The contributing factors for developing ALS are not fully understood. However, in some rare cases, ALS may be inherited. There are generally two types of ALS5:

- Familial ALS

- Affects: 10% of patients

- Cause: Hereditary

- Sporadic ALS

- Affects: 90% of patients

- Cause: Unknown

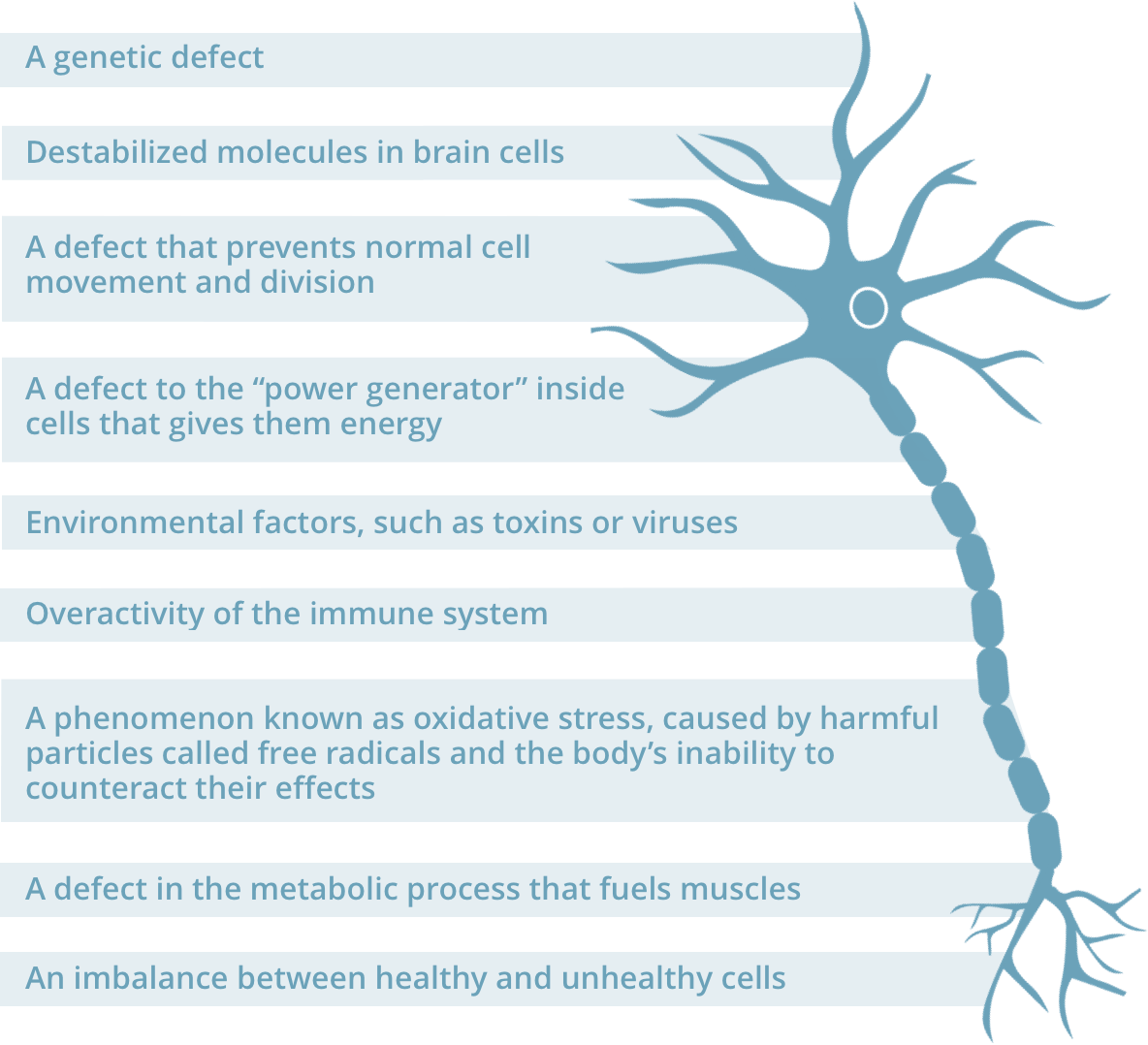

Research suggests many factors can contribute to the loss of motor neurons in the brain, which may increase one’s chances of developing ALS. These factors may include6

Symptoms of ALS

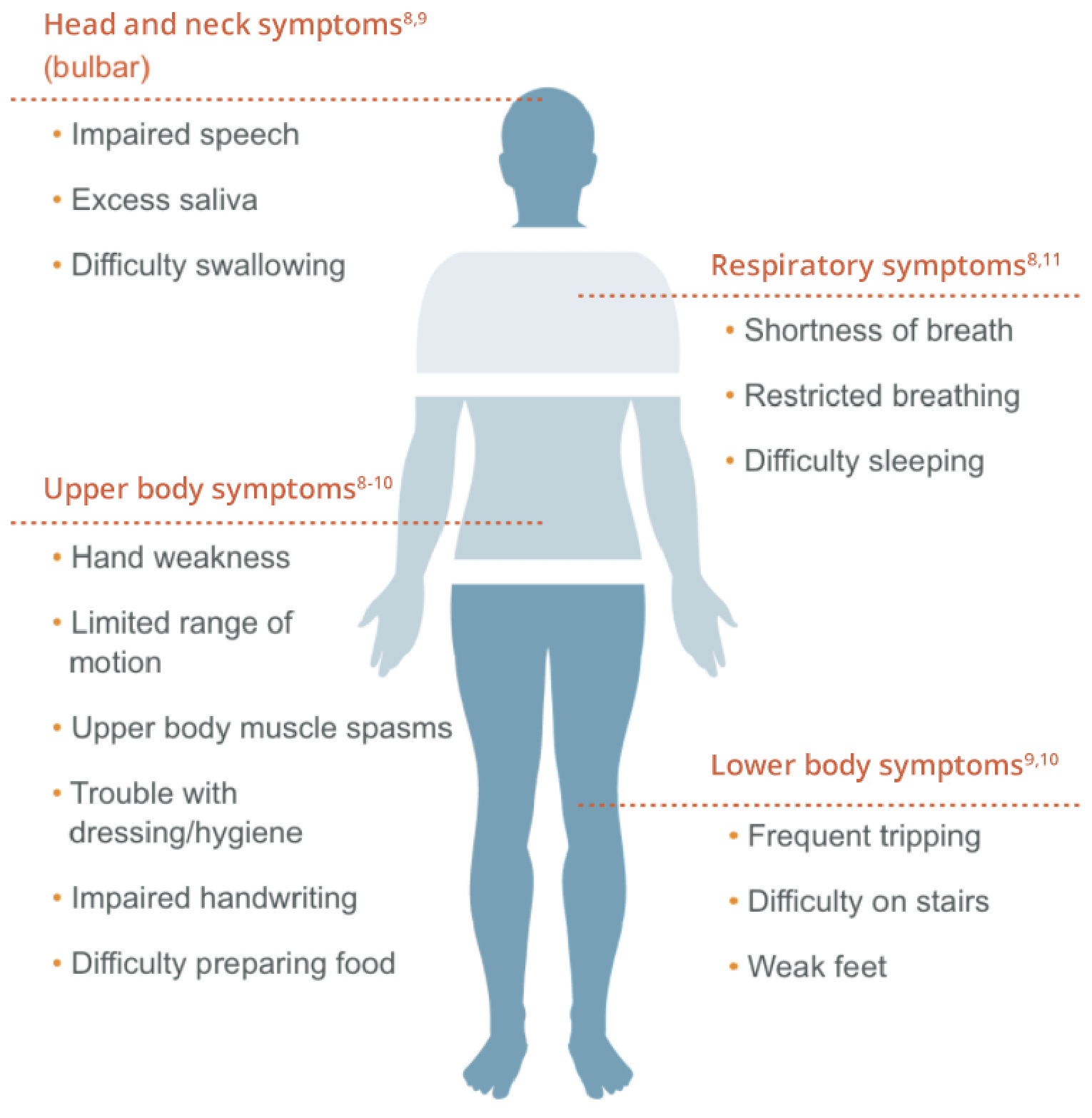

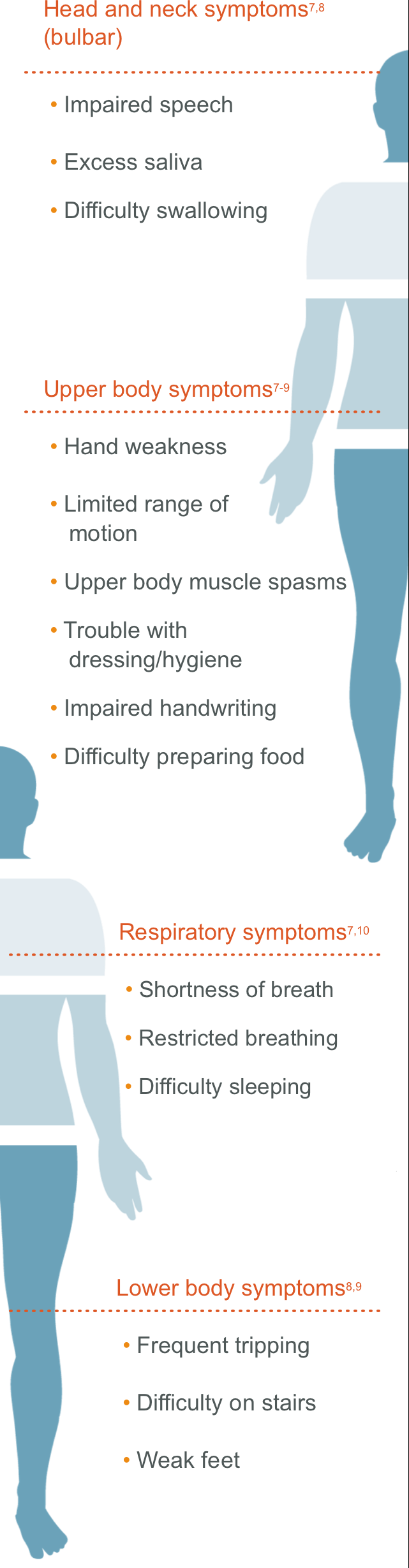

ALS Symptoms Affect Everyone Differently

No two people with ALS are alike. This is because the signs and symptoms of ALS vary from person to person and often affect different regions of the body.7

Knowing which parts of your body are affected by ALS can help you and your healthcare provider(s) better understand how ALS will impact you moving forward.

Knowing which parts of your body are affected by ALS can help you and your healthcare provider(s) better understand how ALS will impact you moving forward.

Two newly diagnosed people with ALS may experience their disease in very different ways. For instance, one person may have trouble grasping a pen or lifting utensils, while another may experience a change in the sound of their voice.7

ALS can progress differently for each person. Some people may first notice changes in their speech or swallowing, while others may feel weakness in their hands, arms, legs, or feet. Not everyone experiences the same symptoms or in the same order. However, over time, most people with ALS will face increasing muscle weakness and loss of movement.7

ALS can progress differently for each person. Some people may first notice changes in their speech or swallowing, while others may feel weakness in their hands, arms, legs, or feet. Not everyone experiences the same symptoms or in the same order. However, over time, most people with ALS will face increasing muscle weakness and loss of movement.7

For many people, there are certain functions ALS does not affect. Most people typically maintain7,10:

Their sight, touch, taste, hearing, and smell

Control of eye muscles, bladder, and bowel functions

Because of the individual nature of ALS, it’s extremely important that you speak with your healthcare provider(s) about all symptoms you may be experiencing.

Tools to Track ALS

How to Track ALS

The symptoms of ALS get worse over time. Therefore, it’s important to carefully monitor these symptoms and track your disease activity. This can help you and your healthcare provider(s) better understand how ALS is affecting your body and how quickly it’s progressing.

Several clinical measures have been developed to monitor your ALS. Some of these include

Several clinical measures have been developed to monitor your ALS. Some of these include

Doctor-administered questionnaires ask people with ALS to rate how well different muscle groups are working, based on a sliding scale. The individual scores for each muscle group are then tallied, providing a high-level assessment of overall muscle function.

The most well-known questionnaire is called the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R).

The most well-known questionnaire is called the ALS Functional Rating Scale-Revised (ALSFRS-R).

Since muscle weakness is a major feature of ALS, measuring strength over time can help your healthcare provider understand how quickly ALS is progressing. The most commonly used strength measurement is called handheld dynamometry (HHD). During HHD, the examiner holds a small gauge that the patient pushes against using different muscle groups.

As respiratory (breathing) dysfunction remains the most common cause of death among people with ALS, assessing lung function is extremely important. A forced vital capacity (FVC) test is typically used for this. A FVC measures the maximum amount of air a patient can exhale from their lungs after taking the deepest possible breath.

Ask your healthcare provider(s) about different measurements to track your ALS.

References: 1. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) fact sheet. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/sites/default/files/migrate-documents/ALS_FactSheet-E_508C.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed October 14, 2025. 2. What is ALS? ALS Association website. https://www.als.org/understanding-als/what-is-als. Accessed October 24, 2025. 3. Basic Facts about MND. Motor Neurone Disease Association website. https://www.mndassociation.org/about-mnd/what-is-mnd/basic-facts-about-mnd/. 4. Who gets ALS? The ALS association. http://webco.alsa.org/site/PageServer/?pagename=CO_1_WhoGets.html. Last updated May 2019. Accessed October 14, 2025. 5. ALS and Genetics. ALS United Rocky Mountain website. https://alsrockymountain.org/understanding-als/genetic-testing-for-als/. Accessed October 14, 2025. 6. Beghi E, Mennini T, Bendotti C, et al. The heterogeneity of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: a possible explanation of treatment failure. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14(30):3185-3200. 7. Symptoms and diagnosis. ALS Association website. https://www.als.org/understanding-als/symptoms-diagnosis. Accessed October 14, 2025. 8. Cedarbaum JM, Stambler N, Malta E, et al. The ALSFRS-R: a revised ALS functional rating scale that incorporates assessments of respiratory function. J Neurol Sci. 1999;169(1-2):13-21. 9. Mitchell JD, Borasio GD. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 2007;369:2031-2041. 10. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic website. www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/amyotrophic-lateral-sclerosis/symptoms-causes/dxc-20247211.2016. Accessed October 14, 2025. 11. Symptoms. ALS Canada website. https://als.ca/what-is-als/symptoms/. Accessed October 14, 2025. 12. Rutkove SB. Clinical measures of disease progression in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12(2):384-393.